July 17, 2025

From Periscope House to Material Futures: A Dialogue with J. Jih

Inside the Flow: How Periscope House Shapes Movement and Privacy

Dancers sometimes speak of the incredible focus required to perform at their best… of proprioception, a sense of their own bodies and of their fellow dancers. The owners were interested in sourcing FFE themselves; fixtures, appliances, and hardware were all carefully selected to preserve an atmosphere of haven and soft, but deliberate awareness. This brought a precise calibration of their personal sensation through heated foyer floors, indirect lighting in warm color temperatures, and hollow folded metal locksets that are warmer to the touch than traditional solid cast hardware. To this, Jih introduced their formidable spatial literacy to calibrate a hierarchy of social sensation: introducing defined zones of privacy alongside active communal areas. The transitional spaces between them are tectonic in nature – but their liminality is perceptual in nature, too. Ceiling heights double or lower; walls peel back to arm’s reach; daylight suffuses or spotlights; and sonic reflections echolocate, offering spatial cues to indicate that you’ve begun your gathering, or concluded your work day.

The subtlety of such gestures can only be successfully manifested with trust, nimble problem-solving, and consistent, open dialog that not only supports but invites collaboration.

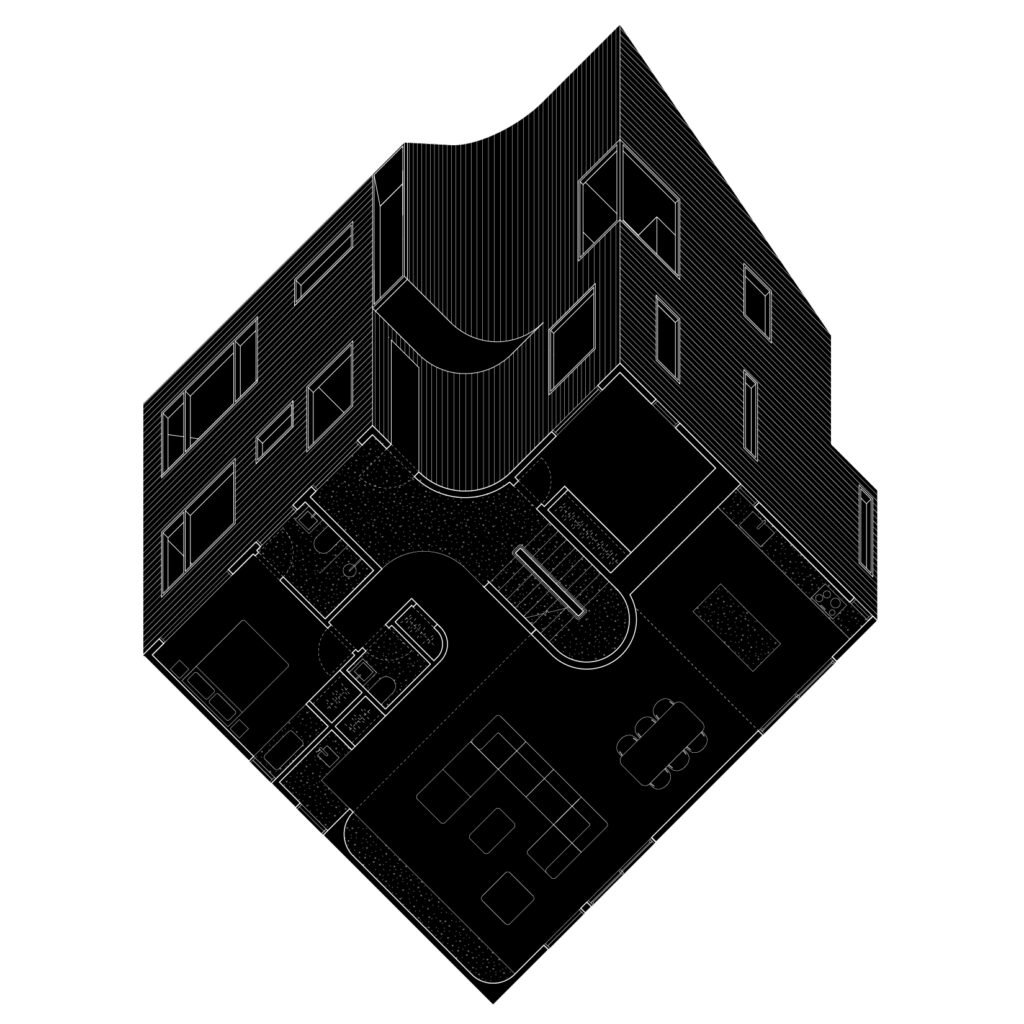

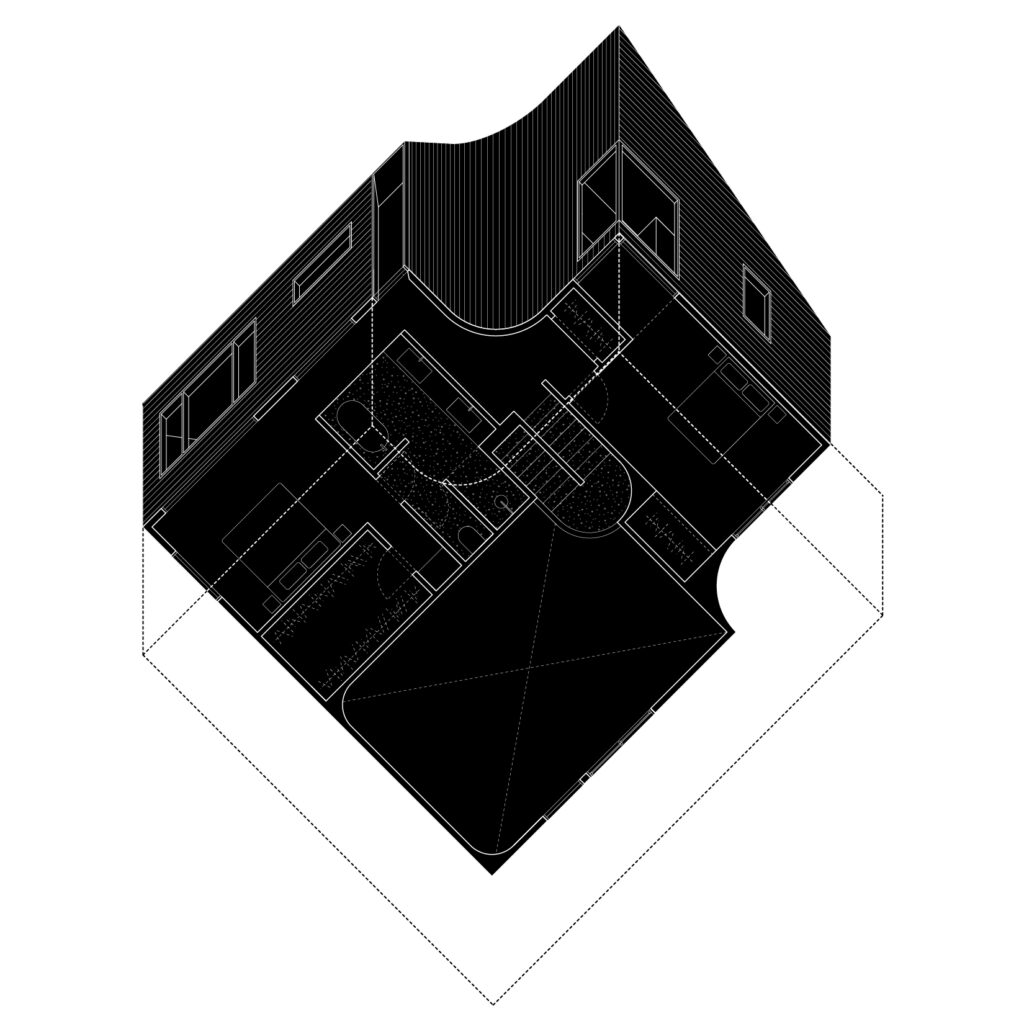

The living and kitchen areas are fine examples of the collaborative owner-architect dialog that resulted in the project’s sense of whole”? : the owners were cognizant of the efficiency triangles that govern kitchen design and sought a compact galley configuration to maximize the dining area. Jih encouraged them to reconsider, shifting and enlarging the island to afford space for informal gathering before a social meal… to celebrate the act of cooking that the owners enjoy… but also, to allow two people to pass one another on the working side easily.

The edge of the island is reinforced by a ceiling height transition, and the point of inflection in a wall that arcs away to hug the stair. Move out from under the lower kitchen soffit, and you see the long, high slot of a window above the living room’s quasi-hearth – through which you can glimpse the komorebi of neighboring trees, or, at serendipitous passing, the alignment of a perfectly framed full moon.

Periscope House is full of these moments that reveal themselves diegetically, which makes it all the more special since such details are challenging to resolve at all, let alone well. They are a tribute to the designer, of course, who can gracefully but boldly weave them into the fabric of a house that upholds the privacy aspect of its dual nature… and to the contractor who can see the vision successfully translated from the virtual to the physical… but also to the owners, who had faith in the concepts and skill, and their own ability to express themselves through the complex and intricate steps of architecture.

It’s a thing of beauty.

A Conversation with J. Jih

Linda Just (LJ): I was reflecting on the project brief and images of the Periscope House in conjunction with the Es Devlin talk that occurred at MIT last night. The train of thought reminded me of a lingering preoccupation I have with houses as stages for everyday drama (in the sense of a play, not as in the negative connotation), and how this may inform design. And also the fact that a space itself almost acts as a character within everyday rituals and performances. There is something about the photos of this house that recapitulates those things. There’s an implied quality of heightened experience through simple gestures.

Is that something that you find as a theme within your work?

J. Jih (JJ): I’ve always had an interest in scenography, so I absolutely consider the choreography to be of importance when I’m designing at the residential scale. Particularly in this house, it’s tied to larger urban dilemmas of a densifying and expanding urban perimeter, which is a paradigmatic concern for a lot of periurban places right now. And so I find choreographing domestic life in a compact context to be quite interesting and at the heart of a lot of the house projects [I do].

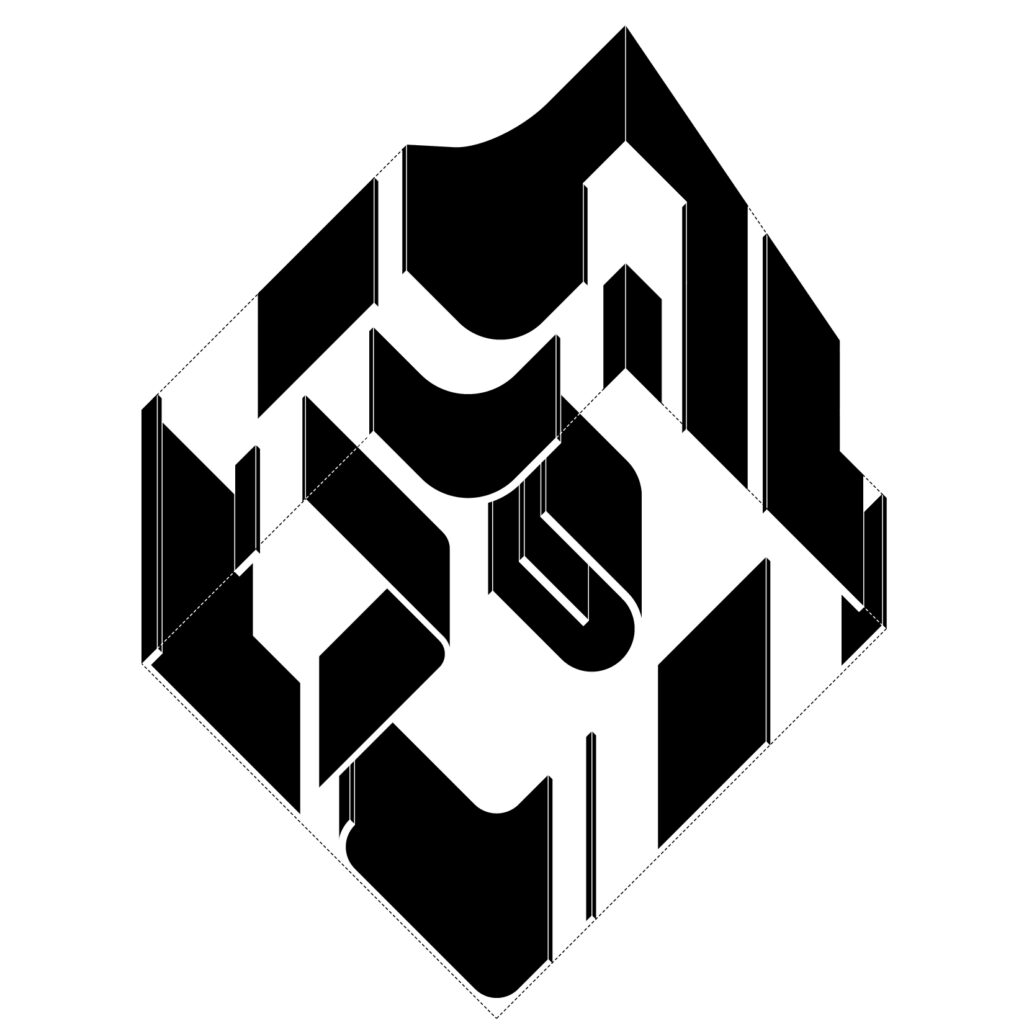

The whole motivating idea behind Periscope House was its extroverted views and introverted privacies. In Oblique Figures, there was thought about the perceptual readings of circulation, very literally from different perspectives. Hairpin House combined choreography with a solution for [the] program within an incredibly tight envelope.

Though I would argue the lens of typology is beginning to disintegrate as a strict conversation at the residential scale, but there’s that, too. It crystallized in the Crown House, which I had done together with Sean Canty, though in that case it’s more an intersection of typology and these domestic choreographies, expressed as design in simultaneous plan and section, with a process that was able to transform both.

So I think you’re definitely identifying a core set of interests within the balance of both a sensitivity and care for the intricacies of domestic life and a desire for meaningful formal or typological expressions.

LJ: The notion of care and meaningfulness is such a generous approach to housing. In architectural pedagogy, discussions around typology tend to be a great leveling factor, but that vehicle in the program of the residential is tricky, right?Because everybody’s needs and habits are a little bit different. That care or nuance would be so vital to keeping everything fresh and responsive to any users, I’d imagine.

JJ: Yeah. I think the locus of meaning in work of the residential is not often regarded with as much importance as larger-scale programs, with which most material- and construction-based research is typically associated. However, I quite enjoy examining a level of specificity through choreographed narrative as well. And it always ties back to constructively inform the larger-scale work, too.

LJ: So with that in mind, is there a typical entry point for you to examine someone’s domesticity and develop your vocabulary as you translate it into a form? I’d imagine when you approach a new project with a unique client, not everyone is as aware of the confines that would, in effect, inform choreographies that you would encourage, complement, or alter. Is that something that you could say more about?

JJ: I’m not sure if there’s a precise methodology. I think it begins with just a conversation to try to empathetically know who you’re speaking with. For instance, I’m chatting with new clients who are a nuclear physicist and a biochemist working on the fusion reactor. They’re really fascinating, and we spend a lot of time just talking about snapshots of their imagined life in the next decade. We’re getting to know how they live in a day, a month, a year… and the idea developing now is of a tree, planted at the same time we build a house.

The two will begin by indexing time across one another by marking seasonality, the birthdays of children, and developing the concept even further from there: how would you relate to the exterior? How would you open a window? How does that view change over the course of four seasons? It’s very specific and very poetic.

Much the same in Periscope House.

There, we talked especially about ideas of privacy and view, and that amidst everyday life, there are also these intensive moments when the clients wanted to be reading and have space and privacy to do that, or to introspectively look over the horizon. These perceived conditions were developed into vignettes that we began to storyboard: activities of seclusion, ofviewing, of cooking, of coming together, and then being apart.

Diagrammatically, they formed a series of almost curving linkages that at times started to skirt and merge with each other.

While it’s always a danger to interpret a diagram too literally, in this case, that form of turning became a really key idea in the project.

LJ: The curvature portion of things is very interesting in the Periscope House. It is noteworthy but subtle. I often wonder how to successfully work a move like that into a project like a house, where you have such a small footprint and some very basic practicalities that you have to embrace.

As interesting as a fully nautilus-shaped house could be, there are some practical challenges that might defeat the proposition. But, these partial punctuations are quite intriguing. So, to hear you so eloquently address the gesture verbally, unbidden, is wonderful. I wanted to ask where it came from!

JJ: I’d say there are maybe a few answers ranging from the pragmatic to the biographical to the thematic.

LJ: So it’s a leitmotif, but it’s subtle. Does that vary for you from project to project–emerging as a byproduct of conversations–or is it more complicated than that?

JJ: On a pragmatic level, I think curvature can produce so many soft gradients: of transition, of lighting effect, of orientation. It’s a very simple move that can produce a sense of transition that functions softly in relation to the body. In Periscope House, which was very pragmatic, shaving out the corners of the stair volumes gave us more square footage and smoothed the circulation of turning into the kitchen. On the second floor, the main periscope above the front door is a square footage bonus where we were otherwise constrained in the building footprint we inherited. The move allowed us to have a more functional hallway, instead of just a brutal termination at the corner. So I think in the specific case of this house.

Biographically, I think a lot of my early architectural training was about geometry. A lot of the courses that I teach now are about form and its calibration, including one called “Cultures of Form” that attempts to broaden the terms by which we understand positioning beyond canonical architecture – which is relatively technocratic and looks to geometry and form as simply one disciplinary culture.

I hunt for ways to think about form that are more expansive and inclusive than the lineages that have been given to us. But if we look at affect theory – I’m reading Sianne Ngai’s “Our Aesthetic Categories”– to recalibrate our understanding of space by looking at non-Western aesthetic categories, or terms for scholar’s stones, which are a non-Gestalt, non-Western paradigm, we can see form based on porosity, slenderness, openness, or texture. So that’s the biographical aspect and baggage I bring to the thinking.

But on a thematic level, I just love a soft surface, and find softness, kerning, or a slight inflection has a great use in many projects. And it also has a kind of subtler accommodation.

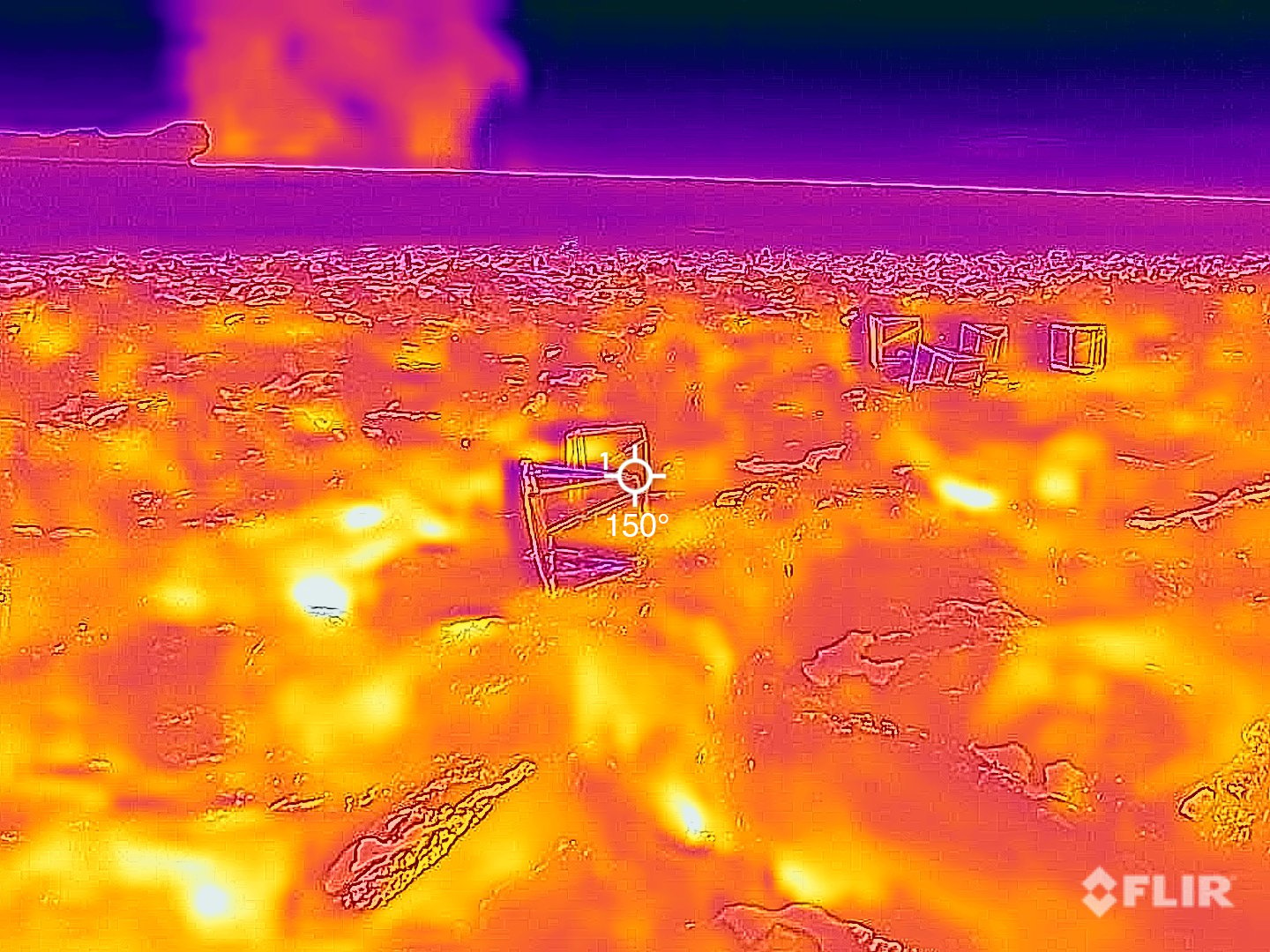

As an example, Skylar Tibbits and I are trying to invent a new, 100-percent stone construction system as part of a grant. We’ve developed these glossy, shimmery, green-gray pillowed walls, made of melted and spun basalt textile.

It’s beautiful material, almost resembling the fabric of cast concrete walls that are relatively familiar to us, but it’s basically a dress pattern for a jammed gravel structure inside. There, the softness is a material register, but not a mannerist or a given conceit. I enjoy that imprint of the material tendencies–it tells you a bit what’s inside the wall.

Skylar’s research while at the ETH was on structural jamming, which produces a strong but efficient assembly. The only issue is its delicacy; you touch it, and the gravel can crumble. I’ve come in and fitted garments to it, giving it a protective skin. Our next step is going to be a composite cladding system with insulation, which will give some more puffiness as well. It’s a down coat.

LJ: I want to ask you more about that notion of calibration of form because it implies a sort of rigor in assembly that is very legible in the character of your projects. But you also speak about these terms like softness, slenderness, shadowing, and shading. Those are precise things linguistically in that we can all evoke a sense of what they mean, but they’re also personal and subjective. There’s a variation–you can’t really pin it to a wall.

It’s a fascinating paradox that you’re making very efficient spaces that evoke the imprecise… and really kind of beautiful metaphor for being alive.

JJ: I disagree with the implicit boundaries that exist in so much of practice and academic discourse. I think that community- and care-based work is incredibly precise, and that it does require calibration. But I resent yielding it purely to the technocratic spheres. So, looking at scholar’s stones as these incredibly calibrated, attuned objects, which are evaluated holistically, has been a reference point in design for me for a long time.

I grew up in Taiwan and China, and spent time in stoneyards as a child, but it didn’t really hit my architectural funny bone until I read Herzog + de Meuron’s monograph Natural History a while back. They wrote an essay about their obsession with scholar’s stones, and it sort of hit me.

They wrote about their qualities as both an inherited and a designed object–something between natural and artificial that is in some way very much the Carlo Ratti intellighenzia theme of the Biennale, but on the level of frameworks of formal analysis.

LJ: I was recently doing some side research and came across the whole ORCA and MAMMOTH projects that Climeworks is running in Iceland, where they’re producing these stone-like samples from the CO2 they’re harvesting from the air. Are you in touch with that organization? I feel like they would find your work fascinating.

JJ: We haven’t yet, although just Skylar and I have just started talking to proper material scientists at MIT to see where the overlap might be. They’re looking at exactly those kinds of research topics, and that’s the next level of inquiry. As a practicing architect, I brought a framework to the research that globally examined how stone is increasingly used,and cataloged its potential. A lot of basalt applications of were an American classified military secret until the 1990s, but it had percolated into the public market: there were geotextiles (which are made of basalt) and cast tiles, which are amongst the most resilient and durable flooring tiles for houses and hospitals. Many institutional buildings from the 1950s had basalt tiles because they’re essentially vitreous, as basalt has such a high silica content, but were cheaper than qualityglass or porcelain. In recreational applications now, you see basalt tripod legs and kayak oars as far less environmentally damaging than fiberglass or carbon fiber versions.

We found all these things that existed at different scales and in different industries, but were not normalized as architectural construction material. And I realized that almost without even needing to invent new processes, we could situate ourselves between architectural practice and academics and create a catalog of parts for a wall section.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Viewpoints

The End of Net Zero as We Know It

Architect and climate strategist Anthony Brower explains how the current language of Net Zero is a “good idea worn thin by its own optimism.”

Products

Feria Hábitat València 2025 Exhibits the Best of Spanish Craft and Sustainable Design

Despite a delayed opening due to weather, the Valencian community’s annual furniture show returned with record numbers.